|

TRIBUTES

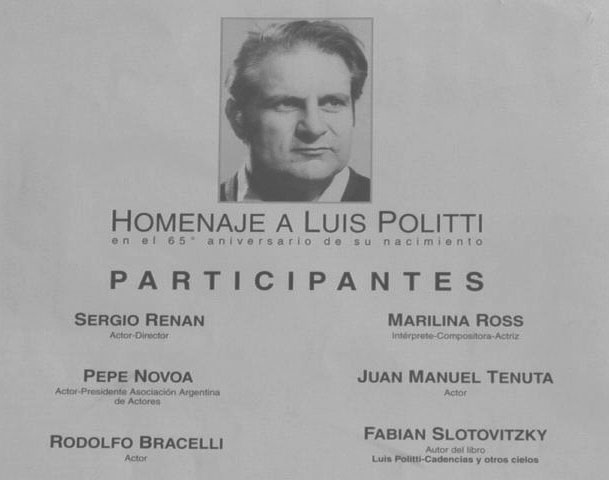

Since his death, friends and fans have paid homage to Luis Politti on numerous occasions, many times through very carefully organized events. One such example was the presentation of the book “Luis Politti: cadencias y otros cielos” by Fabián Stolovitsky in 1995, which took place in the main room of the La Plaza theatrical complex in Buenos Aires and hosted four hundred people, among them Miguel Angel Solá, Juana Hidalgo and Juan José Jusid. On April 8, 1998, Sergio Renán, Marilina Ross, Pepe Novoa, Juan Manuel Tenuta, Rodolfo Bracelli and others gathered in honor of what would have been his sixty-fifth birthday at the Margarita Xirgú Theater. The city of Mendoza honored Politti by naming an auditorium in the municipal theater after him. At present, a documentary is being made which will feature over forty-five of his friends and followers paying tribute to him with personal testimony.

On July 14th of this year, the 25th anniversary of Politti’s death, those who do not want his name to be forgotten plan to host various tributes to his life in Buenos Aires, Mendoza and Madrid.

Some examples of pieces written in Politti’s memory follow:

Politti’s Three Deaths

I had the unfortunate privilege of informing everyone who knew you here in Mendoza of your death. I suppose it was fate since you were the first person I worked with when I arrived here. I met you one day, about eighteen to twenty years ago in what was then called “Al café.” And I got to know you – your work in the university cast, your television program (“Don Julio Pérez” I think it was) and your plans to start a radio-theater piece by Alberto Migré in Nihuil. I also knew that you were married and had kids. Not long after, I would go over to your house. You were the first person in Mendoza to invite me to dinner. And I remember that night well because I walked into your house, looking forward to seeing what you had done and you reproached me for coming ‘here?’ to do theater rather than continuing to struggle in Buenos Aires.

Back then, emigrating was the last thing on your mind; you were a television star here with excellent prospects. Dreams. And yet you were headed towards your first death.

Having a house, a wife, kids, your mother under your care, and a senile father was too great a burden while trying to practice our profession with dignity. How to keep up the house and afford the food, the clothing…?

Those first years of television used and abused you and then let you go. With radio it was the same story – and it is not even worth mentioning the university “salary.” I witnessed everything. “Go on and take it don Luis”… “I will just jot down here what you owe”… “I left home without my wallet, could you…”… To the man at the grocery store and the man at the kiosk, you were Politti, the television star, the radio star and the university man.

And the circle kept on closing in…a desperate turn to gambling as a last recourse…and the never-ending agony…then finally, you left, YOU LEFT! Leaving was the only possibility. That was how they killed you the first time.

The city that killed you applauded you but would not feed you. She flattered you but would not insure your house, the roof over your head. You were an actor, a luxury too onerous to keep alive.

“What was that guy thinking?! Live here with that profession?!” This is the land of vineyards and fruit trees and minerals and real work…What were you thinking? That because they waved to you or clapped for you or asked for your autograph…? Get out of here…

And you went, and you died your first death.

And your second death started there in Buenos Aires. With a little scholarship to help you through your first days there…and all the prostitution of your talent… go see him, go see her. The idiots of television…the coaches: ‘You need to learn technique’… Not to mention that you had nothing of that homosexual, leading-man look. It was bound to be tough, you know…You only had that thing they call talent to help you become the actor that you were as well as a dignified professional. It was a slow process but you did it. And your name started appearing among those of the truly authentic personalities, and that harsh and generous Buenos Aires adopted you with her applause – an applause whose price would force you to leave pieces of your life behind…

You returned a couple times during those years in the capital to visit San Martín, the street your feet had walked up and down so many times before. I remember how those who only yesterday had sacrificed you, were there, submissively, paying you tribute.

You had come to be, then and forever, Luis Politti, AN ARGENTINE ACTOR.

And, from the very moment that you won this title, the insanity of the Argentine people would trap you and you would die once again. For the second time! Don’t you ever learn?! Didn’t you realize that their yelling for you and proclaiming you as a professional and an artist wouldn’t be enough? You were so naïve. Nevertheless, your name and talent would be great enough to get you through this second death – enough to help you go on to become a Mexican or a Spaniard and start over, grow old in glory and in peace, doing what we do.

In Spain, your third death would find you and hold you captive, definitively. But don’t be too distressed, Luis: on stages everywhere there will always be many of us, trying to make sure that your deaths are never repeated. Amen. Cristóbol Arnold, Actor (1929-2003)

In 1954, Luis Politti had just finished his military service. It was the moment to plan out what he would do next and he did not think twice about asking for help from the director of the School of Music at the Universidad de Cuyo.

He had been a terrible student during his rural childhood, during which he spent much of his time riding horseback on his grandfather’s farm, armed with an insolent attitude. He had never wanted to go to school.

He made educational amends as he crossed the threshold of adolescence. While completing high school, he delved into his study of music. Like many other children in his neighborhood in Mendoza, he had started to learn piano at a young age. A woman who lived on the same block offered classes in her home, though more as a distraction than for anything else. Most of her students gave her a little cash gift at will for the holidays – those who were serious that is.

From piano, he moved on to the clarinet and was sought out by young groups and more than one orchestra that would play at the town dances. Later a pulmonary affliction would force him to once again change instruments and this time he chose the contrabass, one of those enormous instruments whose owners envy violinists when it comes time to move them from one place to another.

The Director of the School of Music at the Universidad de Cuyo grew to respect and very much value Politti’s acting at the vocational theater in Mendoza. He did not doubt for a second recommending him to Galina Tolmacheva, who had trained under Stanislavsky and mastered his method. The brilliant young man, just out of the service, would become her beloved pupil.

In 1955, Galina Tolmacheva left and Politti, still a student, was given a paid position. This would give him a means to survive but certainly did not eradicate any economic hardship. The situation in his house was similar to that of any other supported by the wages of a blue-collar worker.

In 1962, Mendoza finally started its own television network. At that time, Politti was the most well known local actor, squabbled over by independent casts, respected by the critics and followed by the public. Television devalued his status as the intellectual actor who had a halo over his head did all the famous playwrights’ works. On the other hand, it gave him a popularity he had never dreamed of achieving in his home province.

He was the big hit on the first live program to air on the local television station, when he played his character “Don Julián Pérez Etcétera.” The latter was a retired widower from Spain who carried on indescribable “dialogues” with a small bird, his only companion. The success he achieved on television in Mendoza pushed him to give it a shot in Buenos Aires, the city that had already turned its back on him on a couple of occasions. During the first half of 1964, he made his definitive move to Buenos Aires, Argentina’s capital. This time he went with a scholarship and endorsement in hand, thanks to the generosity of the National Arts Fund. Pedro Escudero, who had seen Politti’s work in Mendoza, gave the latter his first opportunity on “El vicario.” That was the key that would open the door for the actor.

The rest proceeded in a hasty manner. He debuted on Channel 13 with a cameo appearance – a sort of test run for him in front of the camera – on “Las tres caras de Malvina.”

That small intervention would push Luis Sandrini’s wife to offer Politti a position as “permanent collaborator.” Later would come his memorable work in three programs: a series by Rodolfo Bebán, “Las grandes novelas” and the great hit soap opera, “Rolando Rivas, taxista.” At that point he had already joined the full-time cast at the San Martín Theater, where he would remain for five years. His peers deemed him “wanted” when it came time to putting a cast together. His commitment to his profession was as strong as his commitment to his life, and his life was one that would never sell out, not even when the price meant exile from his country. And his exile was one he could not manage; it would drive him to his death.

Roberto Quirno

|

|

Home

| Biography |

Artistic Training |

Theater Mendoza |

Television in Mendoza |